Across the United States, expansive soils cause $13 billion in annual damage to buildings and infrastructure (Puppala & Cerato, 2009), and the South is not immune to this risk.

Arkansas, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama all sit atop unique geological deposits that are prone to shrink–swell behavior, which cracks foundations, damages buildings, and reduces a structure’s usable lifespan.

Yet, despite these challenges, there are proven solutions for building on top of shrinking and swelling soils. Simple, cost-effective, and already proven under 178+ million square feet of structures in North America, VoidForm is helping developers, engineers, and contractors mitigate risk across the highly expansive regions of the South and the Gulf Coastal Plain.

Lessons in Data

Center Construction

Across the South, agricultural land is rapidly being developed, and with development comes the challenge of expansive soils. From homes and schools to hyperscale data centers, every project is at risk when foundations sit on expansive clay.

Our case study, Lessons in Data Center Construction: Rural Land is Cheap. The Soil Can Be Costly, shows how some of the world’s largest companies are tackling expansive soils without relying on costly over-excavation or chemical stabilization, and why the exact same solutions protect projects of every size.

See how engineers and contractors are addressing the expansive soil issue across the South.

From Arkansas to Louisiana:

Expansive Clays of the South

The landscape of Mississippi may feel markedly different from that of Louisiana or nearby Arkansas, but the geological formations underlying much of the South share one common element: their highly expansive nature.

Expansive soils are clay-rich formations classified based on the significant changes in volume (swelling and shrinking) that occur with exposure to moisture. These soils are characterized by their high content of expansive minerals (like smectite and montmorillonite), which have crystal structures that readily attract and hold water molecules between their layers. This trapped moisture creates a swelling effect, which shrinks when the clays dry out.

The degree of volume change depends on the soil’s mineral composition, but in extreme cases, expansive soils can swell by as much as 200%. Whether it’s 10% or 200%, this expansion exerts enormous upward and outward pressure on buildings, infrastructure, and other critical structures.

Here are a few of the most prevalent types of expansive soils found across the South. Each has its own unique characteristics, but they all share the potential for causing devastating structural damage due to their powerful shrink–swell potential.

Blackland Prairie Soil

Blackland Prairie Clay (also known as Houston Black soil) extends from Texas into Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, western Georgia, and parts of Kentucky. It forms narrow belts derived from ancient Cretaceous clays.

The soil is alkaline and dominated by montmorillonite minerals, giving it a high shrink–swell potential. When wet, it becomes sticky and difficult to work with; when dry, it hardens and cracks. Poor natural drainage exacerbates the problem, resulting in high runoff and slow absorption in moist conditions.

Despite its challenges, Blackland Prairie Clay has historically supported productive farmland and remnant prairie ecosystems. But for engineers and builders across the South, its expansive nature remains one of the main geological risks that must be addressed well before construction begins.

Porter’s Creek Clay

Porter’s Creek clay is a major formation in the Mississippi Embayment as well as the Jackson Purchase region of Kentucky, with stretches extending into western Alabama, parts of Arkansas, and central Louisiana. It’s found widely across the Southern states.

This clay is dark gray to black in color and composed of more than 80% montmorillonite. This type of clay deposit is highly reactive to moisture, meaning it’s prone to swelling when wet and shrinking when dry. Its high plasticity index and shrink–swell behavior make it one of the most challenging soils to build on top of, putting structures at risk and leading to foundation movement, cracking, and long-term structural damage.

Yazoo Clay

Yazoo Clay is one of the most expansive and challenging soil formations in the southeastern US. It is widespread in central Mississippi, especially in the Jackson metropolitan region and surrounding counties. This clay formation trends northwest to Southeast across the state, reaching into Alabama and Louisiana.

Yazoo clay is notorious for its severe shrink–swell behavior, thanks to its unique composition, which is roughly 30% montmorillonite. It appears yellow to brown when exposed to air and blue-gray in its unweathered state, which is part of the reason it’s colloquially known as “Blue Yazoo.”

Like other types of expansive soil, Yazoo is highly plastic and reactive to moisture. By some measures, it can undergo volume increases of more than 200% and generate pressures of 25,000 psf or more. With deposits extending hundreds of feet deep, traditional mitigation strategies are often not applicable, necessitating alternative structural solutions, like void forms.

Strategies for Building on

Expansive Soils in the South

Arkansas, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama all sit on highly active clay formations that present significant challenges for the engineers tasked with mitigating the shrink–swell risks for the structures built on top.

But with the right strategies in place before concrete is poured, projects can move forward safely and cost-effectively while ensuring long-term structural performance. Here are the three most common approaches to building on expansive soils:

Overexcavation

One traditional approach is to remove the expansive clay and replace it with a stable fill. While effective for shallow deposits, this method quickly becomes impractical in the South, where active clays can extend tens to hundreds of feet below the surface. Also, the volume of soil to be hauled, disposed of, and replaced often drives costs and timelines beyond project feasibility.

Chemical Stabilization

Mixing additives like lime or cement into the soil can reduce swell potential. In the South, however, high water tables, organic-rich soils, and local environmental concerns can limit feasibility. For example, saturated conditions, like those common in Mississippi or Louisiana, can hinder the effectiveness of chemical stabilization, thereby increasing the structural risk.

Structural Solutions

Void forms provide a third, more adaptable option. By creating controlled voids beneath slabs, beams, walls, and piers, void forms create a space for soils to heave into without transferring pressure to the structure above.

Available in materials ranging from biodegradable corrugated carton to weatherproof plastic, VoidForm can be tailored to the local environment, whether managing moisture-rich Yazoo clays or ecologically sensitive Blackland Prairie environments. With a manufacturing facility in Mississippi, VoidForm simplifies material sourcing, making it one of the most scalable and cost-effective strategies for the South.

FAQs

What states have expansive soil?

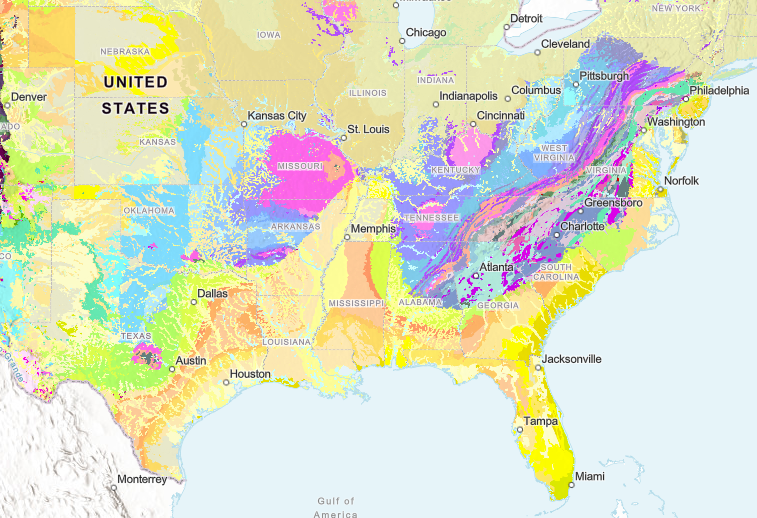

Expansive soil deposits exist worldwide and throughout the US, with notable concentrations in several distinct regions. Damage from expansive soil is widely reported in Texas and Colorado, as well as further east, with substantial areas of Arkansas, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama sitting on top of these deposits. Honorable mentions include regions of the Midwest, including Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Illinois.

The Cooperative National Geologic Map by USGS

Can I build on expansive soil?

Building on expansive soil is possible, but it requires specific measures to prevent foundation and structural damage. A thorough geotechnical investigation is essential before construction. Soil borings and laboratory testing can determine the depth, composition, and severity of expansive soil on site, which will help determine the most appropriate mitigation strategies.

What makes Southern soils especially difficult to build on?

Southern expansive soils are not only highly reactive but also thick and widespread. Porter’s Creek Clay, for example, can reach depths of 200 feet in deposits in Northern Mississippi, making excavation unworkable, while Yazoo Clay can expand more than 200% and exert pressures up to 25,000 psf.

Combined with poor drainage and high water tables, these soils pose unique design challenges for large-scale foundations. Unlike excavation or chemical stabilization, structural alternatives such as void forms are not dependent on local conditions or soil chemistry, making them one of the most adaptable strategies in these environments.

Why don’t traditional solutions like overexcavation or chemical stabilization always work in the South?

On smaller projects, overexcavation or chemical stabilization methods are the traditional strategies for reducing soil activity. Over-excavation requires moving and replacing millions of cubic yards of soil, which drives up hauling costs and project timelines.

Chemical stabilization (lime or cement treatment) often fails in high groundwater or organic-rich soils, and scaling to hypersize projects can push material costs into scarcity pricing. Chemical stability also requires specific soil and environmental conditions to perform properly. More practical in all types of conditions and often more cost-effective, VoidForm offers a broad range of products to protect in and around concrete beams, walls, slabs, and utilities — a proven solution trusted by engineers for over 45 years.

Where is Yazoo Clay in Mississippi?

According to the Mississippi Department of Natural Resources, the state’s Yazoo Clay deposit exists across a northwest–southeast belt that spans nearly three-quarters of central Mississippi. This zone extends across eleven counties, including Yazoo, Holmes, Hinds, Madison, Rankin, Smith, Scott, Newton, Jasper, Clarke, and Wayne.

Does Arkansas have expansive clay?

In Arkansas, expansive clays are most concentrated along an area known as the Fall Line, where Porter’s Creek Clay forms a band stretching from near Arkadelphia to Hope with additional deposits farther north. Other areas of concern include parts of the Western Gulf Coastal Plain and the Red River areas in the far South of the state.

What areas of Alabama have expansive soil?

Alabama’s Blackland Prairie region (also known as the “Canebrake” or “Alabama Black Belt”) is dominated by clay-rich soil\ with high shrink–swell potential. These formations stretch in a belt across central Alabama into Mississippi. The high mineral rich clay content causes the soil to expand when wet and contract when dry, putting building foundations and road construction at risk if not addressed during construction.

What areas of Louisiana are at risk from expansive soil?

Expansive soils are found throughout northern and central Louisiana, particularly in areas underlain by Porters Creek Clay and similar soil types. These clays are highly reactive to moisture and often have poor drainage, making them prone to cycles of heaving and cracking. The Red River Valley and the northern Gulf Coastal area are especially affected, where heavy rainfall and shallow water tables push immense pressures into foundations and structures.